Post45 Data Collective Tabular Data Style Guide

Introduction

In the Post45 Data Collective Tabular Data Style Guide, you will find what it says on the tin: a cheatsheet for how to present and submit your tabular data to P45DC. This guide provides support at multiple points throughout your data journey, whether you are actively making data decisions or have already collected, curated, and documented your data. Though our guidelines are targeted to the latter-end of the dataset lifecycle (specifically storage, publication, and reusability), they will also be helpful for making critical decisions well in advance of submitting to P45DC.

Every dataset is different and will require different decision-making processes. If you are working with data compiled by an external source, for instance, rather than compiling it independently, you might choose to keep the data as-is without standardizing entries per our suggestions in Data Types. Your dataset will not necessarily be rejected for not meeting every recommendation, nor do you need to make every appropriate change before submitting. Our editorial team will work with you to determine what changes are necessary long-term. However, we strongly encourage you to read this style guide well in advance of submission and to use it to guide your decisions.

Is your dataset not tabular (e.g. TEI, visual)? Please reach out to our editorial team before submitting to discuss format and style recommendations.

At the Post45 Data Collective, we aim to make humanities research data accessible, usable, and responsible to its affiliated communities. Our style guide therefore looks to the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, Reuse) and CARE (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics) Principles for data management and governance to guide our recommendations.

Getting Started

- Humanities Data (CDH@Princeton)

- The Data-Sitters Club

- Visualizing Objects, Places, and Spaces: A Digital Project Handbook

- Data Literacies Workshop (DHRI)

- Preserving Your Research Data (Programming Historian)

Tips & Guidelines

- Data Curation Network’s Checklists for Data Curation

- NEH Data Management Plans

- CLARIN (Common Language Resources and Technology Infrastructure) Tools & Resources

- Digital Curation Centre (DCC) Glossary

- Top 10 FAIR Data & Software Things

- The Data Nutrition Project

Data Cleaning & Curation Tools

- OpenRefine

- Breve

- Tidyr (tidyverse suite of tools for R)

- Visidata

- WTFcsv

- Tidy data for Librarians

- DCN Data Curation Primers

Data Management Criticism

General Tips & Suggestions

We recommend the following basic best practices for preparing your dataset.

1. Consider Digital Legibility

Clean your data not just for human readability, but for digital legibility.

Check for unintentional duplicate entries, such as the same author name with slight variations in spelling. To do so, you might use the “Cluster” function in OpenRefine, or a programming approach where you display unique values or value counts.

Remove unnecessary punctuation or trailing white space. Again, this is a task you could complete in OpenRefine (see “Common Transforms”) or with a programming language.

Keep each field as distinct as possible. Ideally, each cell should only contain a single value (though there are exceptions).

2. Consider Use Cases

How do you envision future researchers using your dataset?

If they will use it to generate data visualizations…

- Prioritize sortability

- For example, using ISO 8601 for dates (1794-07-27) allows computers to easily sort them numerically, as compared to other variations (July 27, 1794; 7/27/1294; 27 July ’94) (See Data Types)

- Prioritize consistency and standardization

- For example, data compiled and curated by an external source might include variations in name spelling, formatting, etc. To enable easier and more accurate computational analysis, you will need to standardize the data drawn from these sources (see Data Types).

If they will access it for archival purposes…

- Prioritize comprehensiveness

- For example, if researchers will use your dataset as a finding aid to locate a particular text, you’ll want to include as much identifying information as possible in easily skimmable fields

- For example, if researchers will use your dataset as a finding aid to locate a particular text, you’ll want to include as much identifying information as possible in easily skimmable fields

- Prioritize institutional or item-level accuracy

- For example, a digitized newspaper might spell a person’s name differently than the “official” records provided by external authorities like Library of Congress. Rather than standardizing this data per our suggestions in Data Types, you may opt to retain the variations for the sake of historical accuracy OR include both versions in separate columns.

Who do you envision accessing your dataset in the future?

Be attentive to licensing requirements that might vary based on the accessibility of your dataset.

- For example, if you envision your dataset being free use, make sure to include a non-commercial CC license with your data.

- Check out the Creative Commons Licensing quiz to determine your licensing needs, as needed.

3. Use Appropriate Software

CSV files can theoretically be viewed and edited in many different programs and softwares; however, not all of them will enforce appropriate formatting upon export (see Character Encoding). Avoid working with your data in text editors like Word, and instead stick to programs designed for data work specifically, like Excel , Google Sheets, R and RStudio, or Python and libraries like Pandas.

CSV (Comma-Separated Values) is a non-proprietary format, meaning that you do not need a special piece of software to open it (see File Formats). Rather than saving as a structured spreadsheet, CSV files are plain text files wherein each value is separated by a comma. Learn more about CSV here.

4. Consider Institutional Policies

Are you producing your dataset through a grant funded by an organization like the NEH, Mellon Foundation, or your home university? Don’t forget to follow any of their required dataset guidelines or data management plans (e.g. NEH guide), including requirements laid out by IRB, as applicable (e.g. Emory IRB policies).

5. Document Decision-Making

Document every step of your decision-making process, from the micro (standardizing date formats) to the macro (your approach to determining an author’s gender). In addition to making your research more reproducible, transparent, and reflexive, you will also need this information to draft your data essay for P45DC.

Files & File Organization

File Formats

Ensure that your data files are formatted for sustainable, non-proprietary use. What does it mean for a file format to be sustainable and non-proprietary? Well, a popular file format for working with spreadsheets is the Excel default that ends with the extension .xlsx. This is the default format when saving data in Excel. While .xlsx files can be very useful, they’re technically proprietary and owned by Microsoft, meaning that we can’t rely on them to be accessible forever outside of Microsoft’s ecosystem.

By contrast, a non-proprietary format for spreadsheet files is .csv, which stands for comma separated values. You can open a .csv file with virtually any software package or tool, and they have a better chance of being accessible in the future. You can easily save your spreadsheet in this format, even if using Excel, by clicking “Save as…,” browsing the “File Format” drop-down, and selecting “CSV UTF-8.” One of the only drawbacks here is that you will lose any bells-and-whistles added with Excel, like colors added to cells or special filters.

| Data Type | Proprietary Formats | Non-Proprietary Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Tabular Data | xls & xlsx (Excel) sxc, ods (OpenOffice) | csv |

| Text Data | docx, doc (Microsoft) gdoc (Google) | txt, xml, html |

| Databases | mat (MatLab) gdb (ArcGIS) | csv, xml |

| Images | psd, psb, acv (Adobe) swf (Macromedia Flash) | tiff, png, jpg |

| Audio | wma, wmv (Windows) mov (QuickTime) | mp3, wav, flac |

Example: A small selection of proprietary file formats and their non-proprietary counterparts

The data tables hosted by the Post45 Data Collective provide options to download datasets as a CSV, Excel file, or JSON file. We provide these options for convenience and because we know some users prefer Excel files. We are able to create these three derivative file formats—CSV, Excel, JSON—from a single CSV file, so prospective authors can simply submit a CSV file when ready (if submitting tabular data). If your dataset is not tabular (e.g. TEI, visual), please reach out to our editors before submitting to discuss format, organization, and naming recommendations. The Data Curation Network provides additional information about file formats.

Representing Multiple Values

Ideally, each cell of your CSV file should only contain a single value. However, if you are including multiple data points in one cell (e.g. a list of names), make sure to use a unique delimiter (not a comma) between each datapoint to ensure future users can split columns easily as needed. We recommend semi-colons (;) or pipes (|).

For example, if you format your name fields as “Last Name, First Name” and include multiple entries in the same cell, you will have the following results when using software like Open Refine or Excel to split a column into multiple columns for analysis.

| Internal Delimiter | Original Entry | Split Entries |

|---|---|---|

| Comma-separated | “Du Bois, W.E.B., Mayhew, Henry” | “Du Bois””W.E.B.””Mayhew””Henry” |

| Semicolon-separated | “Du Bois, W.E.B.; Mayhew, Henry” | “Du Bois, W.E.B.””Mayhew, Henry” |

Example: this is what split columns may look like if you use comma or semicolon-separated internal delimiters

Character Encoding

Have you ever opened up a spreadsheet and noticed that letters with accent marks or other diacritics are… all messed up?

| Correct Character Encoding | Incorrect Character Encoding |

|---|---|

| Louise Glück | Louise Glück |

| Louise Glück | Louise Gl�ck |

Example: this is what character encoding errors might look like

This is a common “character encoding” issue. Character encoding refers to systems that enable computers to represent, you guessed it, characters: individual letters like “a” and “á”; emojis like 💩and 🦭; or symbols like ¡, £, and €. We used to rely on many different encoding systems, but today UTF-8 (Unicode Transformation Format) is the most widely used. It can represent almost any character in most of the world’s languages.

When compiling or working with data, it’s important to save your data in a UTF-8 format and to ensure that diacritics and other special characters are preserved.

It’s very easy for character encodings to get messed up, especially when using Excel. For example, even if a file is correctly saved in a UTF-8 format, if you open it in Excel, the file often will not open as UTF-8 by default. So even if you or someone else correctly preserved special characters upon an initial “save,” if you re-open that file in Excel, the special characters may look garbled, and you may accidentally overwrite the data in this garbled format.

This is a known and notorious problem. Microsoft has offered two suggestions for properly opening a UTF-8 file with Excel. You may also consider working with Google Sheets, which is more easily able to open UTF-8 files, or with an open-source tool like Open Office.

For more guidance on how to convert or properly export a file with UTF-8 encoding, check out documentation on sites like Stack Overflow. If larger-scale fixes are necessary, technical options are available.

Linked Datasets

Does your submission include multiple linked datasets? For instance, “The Index of Major Literary Prizes in the US” includes both a dataset listing the “Major Literary Prize Winners and Judges” AND another listing the metadata for the “Prize-Winning Authors’ Books”—two connected but distinct sets of data. To allow for easy, accessible cross-analysis, please ensure that:

- … cross-listed data like author names are consistent across datasets (or that intentional variations are explained in your data essay)

- … unique IDs do not duplicate across datasets (e.g. same ID for both a line of author data and a line of publication data)

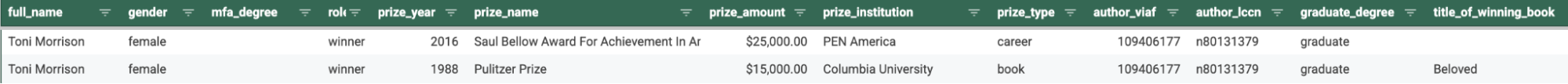

Example: First two entries for Toni Morrison in “Major Literary Prize Winners and Judges”

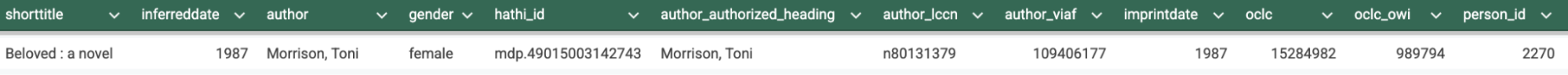

Example: Entry for Toni Morrison’s Beloved in “Prize-Winning Authors’ Books,” a dataset linked to the one above. Though the author and full_name formats differ, the datasets are still easily linked using the LCCN and VIAF ID fields.

Data Structure

Scope

To make your data usable for future researchers, we recommend limiting your scope in the following ways:

Wherever possible, limit data to one value (e.g. one date, one name, or one type of description) per cell. Unlike values should not appear together.

- The decision to include multiple values in a cell is subjective; however, a good rule of thumb is that if you consider each datapoint to be important on its own, it should have its own cell.

- If you require multiple entries for the same category, we generally recommend using additional column headings (e.g. author1, author2, author3) instead of additional values in the same cell. You can see an example in “The Canon of Asian American Literature.”

- Representing overlapping racial or ethnic identity categories in data can be challenging. Post45 Data Collective authors have sometimes chosen to represent these overlapping categories in the same cell, and sometimes in different columns or rows. You can see an example of ethnic identity categories in the same cell, and in separate rows in “Selected British Literary Prizes.”

- The affordance of representing categories in different rows is that it is easier to aggregate and analyze patterns, such as the number of white or Black authors separate from other nationality or ethnicity categories (see Categories).

- The decision to include multiple values in a cell is subjective; however, a good rule of thumb is that if you consider each datapoint to be important on its own, it should have its own cell.

Standardize the type of information included in each field. This is especially important to consider for freeform fields such as “notes” or “description” that rely on a researcher’s subjective interpretation. Instead of putting every piece of information into one field (e.g. notes), split and categorize the types of information being gathered to make them more legible (e.g. physical_description, image_description, advertisements, summary, related_texts) (see Other Descriptive Data).

Example: Note how the “Time Horizons of Futuristic Fiction” dataset separates freeform fields like “notes” and “predictions” based on the types of information they contain

Rows & Columns

The columns of your dataset should reflect the categories of data you have collected (e.g. title, author), with each row representing a single entry (e.g. Beloved, Toni Morrison). For information on formatting row values, see Data Types. The following represents the Post45 Data Collective’s preferred house style:

- All column names should be formatted in snake case (with underscores separating words) and lowercase letters — (e.g. first_name)

- All column names should be specific and unique. For example, instead of “id,” use “author_id”

- All rows should include a unique identifier (e.g. by pub date and author initials: “20010203TP,” a consecutive string: “n1” and “n2,” etc.)

- If referring to a person’s name, please format as “first_name,” “last_name,” and/or “full_name” (see Names, Places, and IDs)

- Avoid abbreviations if possible, excepting those used in external vocabularies (see External Vocabularies & Authorities)

Missing & Unknown Values

Datasets will always contain gaps, whether in missing/unknown information, or in fields non-applicable to a given subject. It’s important to delineate between all of these slight variations to ensure that none of them are conflated with one another.

For instance, you might use the following schema to decide which missing or unknown value format is best for you:

| Example Column | Example Entry | Value Type | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| birth_date | unknown | Unknown Information | An author’s exact birth date is undocumented |

| title_of_winning_book | N/A | Not Applicable to Subject | An author won the award for their career rather than individual book |

| notes | NaN* | Missing Information | No applicable notes included by researcher |

**“NaN” stands for “Not a Number,” and can be translated from coding language into “this space intentionally left blank.”*

Be sure to also check for outliers and inconsistencies across data. If a large chunk of data is missing (e.g. a specific date range), ensure that this is not due to a research gap on your end. Whatever the reason for a large data gap, your data essay provides a useful space to provide an explanation (and, if necessary, a reflection on its potential impact on analysis).

Data Types

The following standards for formatting entries in your dataset will ensure that your data is sortable, machine-readable, and easily parsable for human readers. In all cases, column names may be duplicated serially for the purposes of multiple entries (e.g. genre1, genre 2, genre3) (see: Data Structure).

Note: If your data is intended to be primarily archival, you may opt to prioritize item-level accuracy over standardization (see: General Tips & Suggestions), or to include multiple versions of the same data. Your choices on this matter should be reflected in your data essay.

Names, Places, and IDs

Personal Names

Use one or more of the following:

- 2 columns with headings “first_name” and “last_name”

- 1 column with heading “full_name” or with descriptor by type (e.g. “author_name”)

- Entries can be formatted as either “First Name Last Name” OR “Last name, First name,” though consistency across entries is encouraged

- Entries can be formatted as either “First Name Last Name” OR “Last name, First name,” though consistency across entries is encouraged

- 1 or more columns as defined by external vocabulary, including authority name in heading (e.g. “loc_name,” “wiki_name”, “VIAF”)

| first_name | last_name | author_name | loc_name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ursula K. | Le Guin | Le Guin, Ursula K. | Le Guin, Ursula K. 1929-2018 |

Example: The level of granularity you use will vary by use case

In all cases:

- Ensure variant spellings and versions are standardized (e.g. either “Forster, E.M.” or “Forster, Edward Morgan,” not both)

- In the case of names that may have changed over time (e.g. due to marriage, gender transition, etc.), solutions will vary by dataset and potential use cases. However, make sure that you are consistent with your choice and that you document it in your data essay.

Institutional Names

Use one or more of the following:

- 1 column with heading “institutional_affiliation”

- 1 or more columns with headings by type (e.g. “publisher,” “undergraduate_inst,” “granting_org,” etc.)

- 1 or more columns as defined by external vocabulary, including type and authority name in heading (e.g. “loc_publisher,” “viaf_university,” etc.)

In all cases:

- Ensure variant spellings and versions are standardized (e.g. either “Emory” or “Emory University,” not both)

- In the case of names that may have changed over time (e.g. “Penguin” & “Random House” vs. “Penguin Random House”), solutions will vary by dataset and potential use cases. However, make sure that you are consistent with your choice and that you document it in your data essay.

Geographical Names

Use 1 or more of the following:

- 1 column with heading “place” or with heading by type-variant (e.g. “publisher_place,” “birth_place”)

- 2 or more columns with heading by type-level (e.g. “state,” “country,” etc.)

- 1 or more columns as defined by external vocabulary, including type and authority name in heading (e.g. “TGN_place,” “viaf_country”)

| pub_place | pub_country | pub_state | pub_city |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cincinnati, OH | United States | Ohio | Cincinnati |

Example: The level of granularity you use will vary by use case. In most instances “pub_place” on its own would be fine.

In all cases:

- Ensure variant spellings and versions are standardized (e.g. either “St. Louis” or “Saint Louis,” not both)

- In the case of names that may have changed over time or that they have variant cultural names (e.g. “Okmulgee, OK” or “Muscogee Creek Nation”), solutions will vary by dataset and potential use cases. However, make sure that you are consistent with your choice and that you document it in your data essay.

Unique IDs

Include IDs for ALL external vocabulary or authority terms used in your dataset (see Data Structure).

In all cases:

- Use headings that include type and authority name, and ID indicator (e.g. “viaf_name_url,” “tk_family_id”)

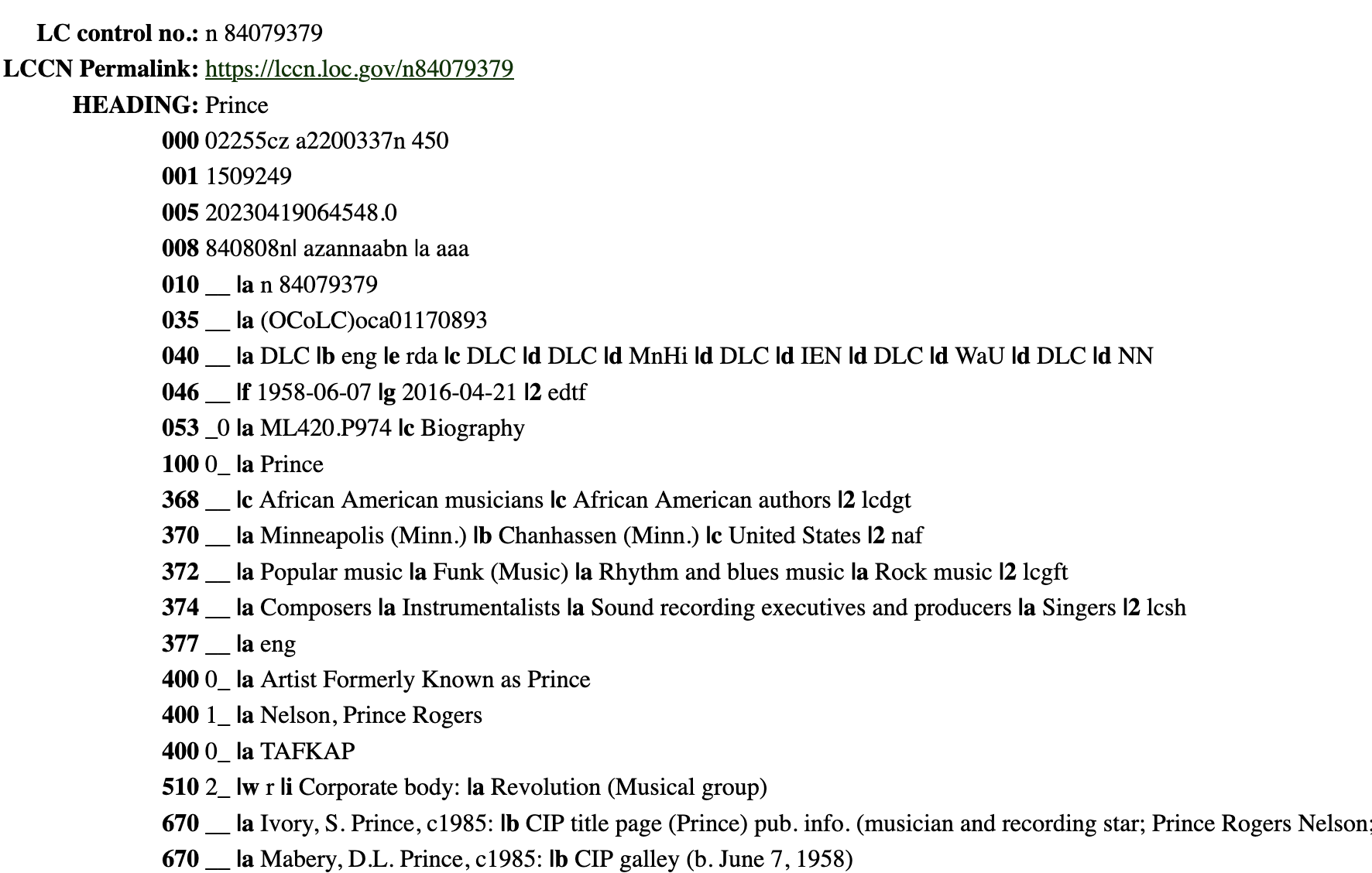

- EITHER use the ID on its own or the URL version of the ID (e.g. “n84079379” or “https://lccn.loc.gov/n84079379.” Be consistent.

| loc_name | loc_name_id | TGN_place | TGN_place_url |

|---|---|---|---|

| Le Guin, Ursula K., 1929-2018 | n78095474 | Cincinnati (inhabited place) | http://vocab.getty.edu/page/tgn/2007971 |

Example: Library of Congress & Getty identifiers

Numbers

Dates

Headings

- Headings will vary by dataset scope and use case. We recommend indicating “type” of date in the heading, especially if more than one date column is present in the dataset (e.g. “pub_date,” “birth_date”)

Entries

- Use ISO 8601 format for ALL featured dates (e.g. “1794-07-27”)

- If only one section of the ISO date is relevant (e.g. publication year), you may shorten to that relevant section; however, always maintain the basic order of yyyy-mm-dd

- You may also include human-readable, “as-described on text” date information in a separate entry (e.g. “July 27, ’94”). However this information should be supplemental to the ISO entry and should be labeled appropriately (e.g. “date_on_text”)

| pub_date | date_on_issue |

|---|---|

| 1976-10-03 | Oct. 3, 1976 |

| 1976 | 3 Oct. 1976 |

Example: two versions of date data. The first (ISO) is required; the second is optional.

Approximations

- ISO and Library of Congress guidelines suggest the following formats for approximate dates:

- To refer to a decade, indicate only the first 3 digits for the year entry, followed by an x for the remaining digit (e.g. “201x” for 2010-2019)

- To refer to a century, indicate only the first 2 digits for the year entry, followed by x’s for the remaining digits (e.g. “18xx” for 1800-1899)

- To indicate that a listed date is uncertain, append with a question mark (e.g. “1603-10-12?”)

- To indicate a listed date is approximate, append with a tilde (e.g. “1794-07-27~”)

For additional variations, including information on formatting intervals, durations, and times, check out this helpful blog post from BASHing data.

Integers

Headings

- We recommend indicating the “type” of integer in the heading (e.g. “no_award,” for number of awards or “bl_id” for IDs registered by the British Library)

Entries

- If integers begin or end with zeros, programs like Excel will often automatically erase the zeroes upon import. To prevent this, we recommend surrounding the integer with single or double quotation marks to ensure the field is interpreted as “text” rather than “number.” We also recommend that you use functions in programs like OpenRefine or Excel to automate this process, rather than adding punctuation manually.

| Original Entry | Excel Import - with quotation marks | Excel Import - without quotation marks |

|---|---|---|

| 000609702 | “000609702” | 609702 |

Example: this is what import errors for integers might look like

Approximations

- To indicate an unknown digit within an integer, use an x for that digit (e.g. “12x” for “one-hundred-twenty-something”)

- To indicate that an integer is uncertain, append with a question mark (e.g. “5,004,236?”)

- To indicate an integer is approximate, append with a tilde (e.g. “23~”)

Publication Data

Contributors

If the publications in your dataset include multiple types of contribution (e.g. edited collections as well as monographs), consider a standardized way to document contributors.

Use 1 or more of the following to identify multiple types and numbers of contributors:

- If you want to keep a single name column, title it “contributor” or “creator” rather than “author”

- Categorize type of role in a separate column (e.g. creator: “Lahiri, Jhumpa,” role: “editor”)

- To delineate within the column titles themselves, include multiple name columns, such as “primary_contributor” and “other_contributors” or “author” and “editor”

Editions

Depending on the scope and use cases of your dataset, it may be useful to include edition data about publications. For instance, if a future researcher wanted to analyze the impact of male editors on books written by women in the 19th century, they would require metadata indicating both the 1818 and 1831 editions of Frankenstein are included in the dataset.

Use 1 or more of the following to identify edition data:

- A column with heading “edition” and entries consistently formatted (e.g. “1st ed,” “first edition,” or “1818 edition,” not all 3)

- ISBN/ISSN, if period-applicable (see below)

Serials / Series

Serialized texts may benefit from using 1 or more of these additional fields:

- A “serial” title column in addition to the main title entry to account for titles of special issues, title changes across time, episodes of a series, etc.

- 1 or more fields for unit release information (e.g. “volume,” “number,” “season_no,” “episode_no”)

- Though publications themselves may use multiple formats for this information (e.g. “vol. II” followed by “vol. 3”), standardize your own formatting as much as possible

- 1 or more “contributors” columns and/or 1 or more “editor” columns (see above)

- If academic journal, include a column for DOI

| ep_title | series_title | season_no | episode_no |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amok Time | Star Trek: The Original Series | “2” | “1” |

Example: entries for a serial publication

ISBN/ISSN

Including the ISBN or ISSN for a publication can make specific bibliographic information more accessible. Tools like our OpenRefine script or citation managers like Zotero can easily automate searches for this information.

When importing this data from other sources, extraneous information is often included to indicate edition information (e.g. “0670030074 (alk. paper)”). For sorting purposes, we recommend trimming this to just the number.

Pagination

More often than not, you will be importing pagination data from a secondary source rather than formatting it from scratch. However, if you are paginating archival materials manually, be sure to use consistent formatting (e.g. “5 pages” or “5 p.,” not both).

If you are concerned about variations and exceptions (a particular problem in historical texts or esoteric genres), library cataloging sources may provide some guidance.

Language

When describing the language(s) used in a publication, use ISO 639-2 codes.

You may also include human-readable terms to describe a text’s language in a separate entry (e.g. “Tagalog” in addition to “tgl”). However this information should be supplemental to the ISO entry and should be labeled appropriately (e.g. “language” vs. “language_code”)

| language | language_code |

|---|---|

| Igbo | ibo |

| French | fre |

Example: two versions of language data. The first (ISO) is required; the second is optional.

Copyright

Depending on the scope and type of data in your dataset, it may be helpful to include copyright information for each text.

- You can find statements to use (and accompanying URIs) here.

- If the item is in the Creative Commons, you can use the statements and URIs listed here.

- If you need to locate the copyright status of a book, NYPL maintains an “unofficial” Catalog of Copyright Entries search interface here.

| title | rights_type | rights_statement | rights_URI |

|---|---|---|---|

| How to Write an Autobiographical Novel | IN COPYRIGHT | “This Item is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this Item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s).” | http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ |

| “Licence to build: Public attitudes to public sector AI” | CC BY 4.0 | “This license enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use. CC BY includes the following elements: BY: credit must be given to the creator.” | https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ |

Example: two variations of copyright documentation

Subjects & Keywords

If you are using subject headings or keywords to describe your data, it will likely be useful to use external vocabularies that have already been standardized and linked across databases (see External Vocabularies & Authorities).

If you choose to generate your own keywords, ensure that you stay consistent throughout (e.g. “LGBT fiction” or “queer fiction,” not both, unless you’re specifically analyzing the difference between the designations).

In both cases, we recommend using keywords only for entry-specific cases. For instance, if every entry in a dataset represents a novel, there is no need to include “novels” as a keyword in every single entry.

Categories

Categorizing your data can bring with it a host of ethical questions. How you decide to navigate these questions will vary based on the type of data you’re working with—if you are categorizing an author’s race, that is likely to be thornier than determining a novel’s genre. Either way, there will always be gaps, problems, and imperfections in our categorization. Be sure to document your decision-making process carefully in your data essay, and account for the inevitable gaps and simplifications in your results there.

Here are a few suggestions for thinking through your categorization schemes in your data itself:

Navigating Taxonomies

Pick a schema based on the objectives of your project and stick to it. If you are categorizing films by genre to analyze genre’s impact on box office success, for instance, consider using industry standard vocabulary rather than more academic terms (e.g. “science fiction” rather than “speculative fiction”); if you are categorizing films by genre to document changes in genre conventions over time, you might expand into sub-categories (e.g. “period film” and “historical epic” for one film, and “period film” and “biopic” for another).

- If your audience is in a particular discipline or community, you might prioritize using categories that will be familiar to them (e.g. Classics of Science Fiction database, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

If your data ascribes identity categories to real people, be thoughtful about your process for determining them. When the person is real (not a fictional character), self-identification should be top priority. Beyond that, your methods will inevitably be imperfect: a person’s race or gender can’t be assumed from photos or names, whiteness is treated as a default and rarely named explicitly, and journalistic coverage can’t always be trusted for accuracy. If your objective is to draw attention to inequality, this categorization is nevertheless important work. Research thoroughly, be critical of your methods as you go, and acknowledge their imperfections in writing, rather than attempting to claim objectivity.

- For example, in Redlining Culture (2020), Richard Jean So uses the following approach: “two researchers had to independently find a scholarly source, or an instance of author self-identification, that marked that author as a specific gender and/or racial category, and the researchers had to agree in their findings. If this standard could not be reached, the author was left unmarked” (p. 194, n. 53).

When describing or categorizing works by marginalized groups, try as much as possible to use vocabularies responsible to and governed by those groups. Traditional Knowledge Labels, for instance, prioritize community-generated and identified language, rather than relying on potentially harmful colonial language to describe indigenous communities.

Other Descriptive Data

Depending on the scope and type of data in your dataset, you may require some fields that are less standardizable than the ones described above. Describing the physical condition or paratextual details of an object, for instance, will require some amount of subjective, descriptive language.

We recommend the following guidelines for fields like these:

Rather than relegating all of this descriptive information to a single “notes” entry, divide them out as much as possible into separate fields. For instance “physical_desc” should be separate from “data_source” should be separate from “researcher_notes” should be separate from “add_info” from an external source. This will make information more searchable and less overwhelming to read.

Even when you’re not listing specific, standardized categories or vocabularies, try to use descriptive, consistent keywords that will help others find your data. Ensure those keywords are sufficient and representative for the subject at hand.

Original Version

| item_id | physical_desc |

|---|---|

| book001 | hinges loose, 225-232 different page color, back flyleaf has doodles. some wear on covers |

| book002 | some pages are loose and brittle, some discoloration throughout, cover and title page are shattering. Book is held in an enclosure and the final page has interesting marginalia. Some pages are stiff and do not open past ~130 degrees. |

Revised Version

| item_id | physical_desc |

|---|---|

| book001 | Damaged copy - pages loose, covers worn; Variant coloration (pp. 225-232); Marginalia - drawings (back flyleaf) |

| book002 | Damaged copy - pages loose and brittle, spine stiff (throughout); Discoloration (throughout); Marginalia - notes (p. 131); Preservation - archival enclosure |

Example: note how the revised version is shorter and easier to read due to its use of standardized language

Acknowledgements

This data style guide draws language, information, and inspiration from the C19 Data Collective Data Documentation guide and Humanities Data Preparation Guide, as well as the Digital Curation Network. Enormous thanks in particular to Sarah E. Reiff Conell, Research Data Management Specialist at Princeton University Library, for her gracious guidance, support, and permissions.

Thank you to the following parties for their generous feedback on this document: Karl Berglund, Julie Enszer, Long Le-Khac, Jordan Pruett, Lindsay Thomas, Ted Underwood, and Grant Wythoff.